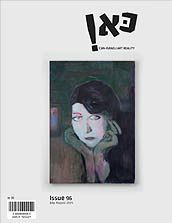

Shimrit Yariv

Veil or mask? Portraiture as dramatic biography – Its all evident in the face / The portraits of Shimrit Yariv

Dr. Nurit Cederboum

Any painting, whatever it depicts, is a self-portrait. This is especially true when the painting declares itself to be a portrait. Pierre Baudelaire, who is described as “the painter of modern life” and “the father of modern poetry” wrote in a letter to Jean Morel, who was the editor of Revue Francaise, that he always felt that a good portrait resembled a dramatic biography, or even more, everyone’s fundamental drama.

Yariv considers man and uses the language of form, with all the various possibilities that this embodies, in order to say things about humanity in general and more particularly about herself. Throughout the long continuum involved in creating a portrait, Yariv collects from here and there to create one new whole in her personal language that becomes her very own unique handwriting and seal. In this space, she moves between the edges; conversing with some sort of photographic truth, maintaining structure, proportions, anatomy. Faithful in her own way to reality and at the same time communicating both with some kind of external reality and also with her own internal reality. Thus, Yariv does not paint a particular person that she knows, rather a person as a symbol, as a container in which she expresses the person that she is, the person within her.

The paintings seem to be composed of layers, like archaeological layers that describe different stages. An innocent stage in which she creates the accurate painting, and after this a “wild” stage that wants to destroy everything and reconstruct out of the devastation. You apparently need to peel off the layer of fluid paint that veils the face like a screen or mask, in order to reveal the clear skin that holds in the internal organs. Yet even while she continues to communicate with reality – inside – she maintains proportion and expression, in other words applying remnants of classical realistic painting, but also brandishes her paintbrush and her spatula to create additional layers of color; thrusts of the brush engender textures and encounters between different forms. Yariv combines different styles and possible expressions and manages to bridge between them, not ignoring the contradiction, yet succeeding in living contentedly and in peace with it – I would say perfectly.

Yariv allows the facial features to communicate, whether it is open eyes or the tilt of a sometimes-exaggerated lengthy neck, closed eyes or gaping mouth and different head postures. Yet in no lesser manner, she uses the language of painting and the medium itself (the paint) as tools to transmit her message. Realism and expressionism dwell together in Yariv’s sketches of the face. In her own way, she uses the face to show not only what exists on the surface, but also what lies below the surface – the inside. Yariv elevates what is usually hidden to the surface, and floods the face of the painted portrait with shaped contents that perhaps reveal what the human skin would like to conceal. In this way, Yariv’s work echoes the work of the English portrait artist Francis Bacon who tried to use his brush and spatula to paint the literal “bleeding flesh” that lies under the skin. This act can be described as presenting a metaphor for the soul. The formative gestures and facial expressions of the painted figures depict mental anguish, something that is hinted just once in the title of one of the works: “The Prophet”, a martyr. The paintings all reflect the suffering of Christian saints of the Middle Ages, recalling mental and corporeal torture, while at the same time they also perhaps intimate the existence of the other extreme, bodily pleasure, even erotica. The facial expressions depict a sort of ecstasy, with sensual brush strokes – of bodies, of the face, of human images that could be anyone, and for the meantime they are also no-one. There is no name; a woman in blue, a man, a woman in green – a name that is absent.

Traditionally, paintings that deal with portraiture aim to mirror a portrayed image. In self-portraiture, this involves facing a mirror, or alternatively observing a model, or in the modern world looking at a photograph. Yariv does not use a mirror nor, it seems, does she use a model, but it could nevertheless be argued that her paintings are actually a mirror reflecting the human story. Art researchers that study the human body and images of man, tell us that the face is the focal point of the body and that its essence is as a form of expression. I would argue that the facial expression attributed to this or that portrait in Yariv’s artworks is not necessarily, or only, the expression of a particular painted image, rather it represents the voice of humanity in the world, relating to moments of excitement or pleasure, desire or disappointment, happiness or sadness, social-gender issues, and relations between the sexes etc.

The fact that the mirror is missing from this body of works, actually indicates its presence, echoing Kleinian theory that talks about the “mirror stage”; an early developmental stage in which the child looks into the mirror and discovers the “hidden other”. Yariv uses bursting color to give presence to the other, who according to Lacan is the “self” that dwells in the deep sub-conscious. Lacan describes the overt as “a veil that hides the beauteous one” assuming that the hidden soul is the beauteous one. It seems therefore that Yariv’s portrait paintings tell the story of that Lacanian veil and the secreted beauty.